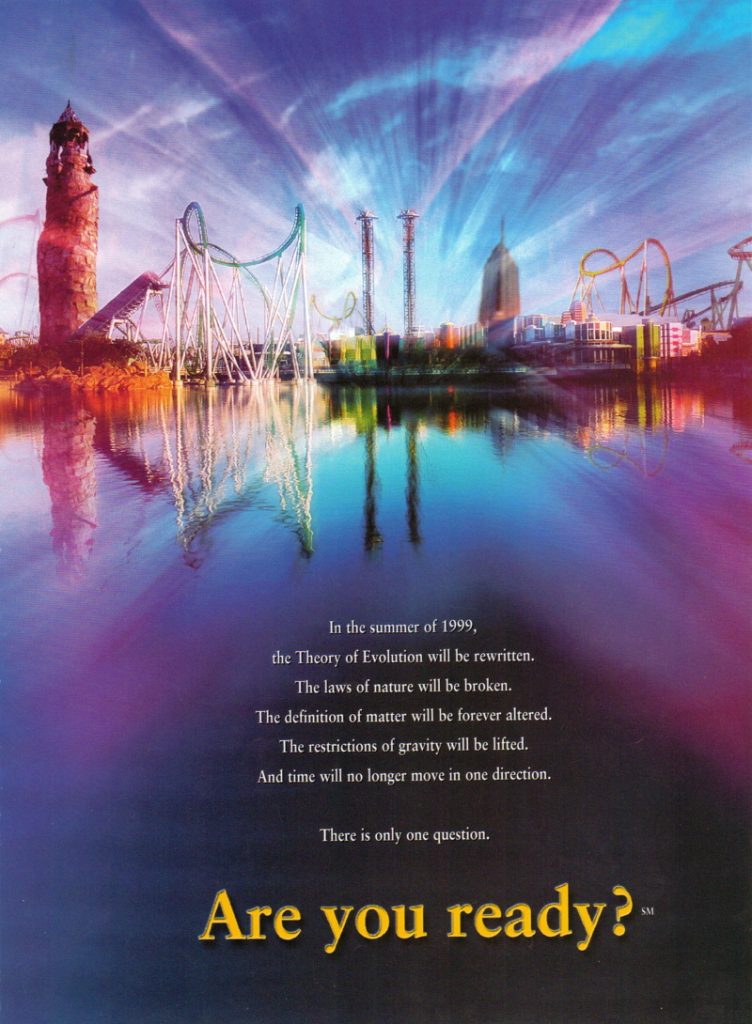

Alexander: It’s 1999. A decade of national prosperity is poised to usher in a new millennium. Everyone is excited. Everyone is spending money. Everyone is ready to grab the 21st Century by the reins.

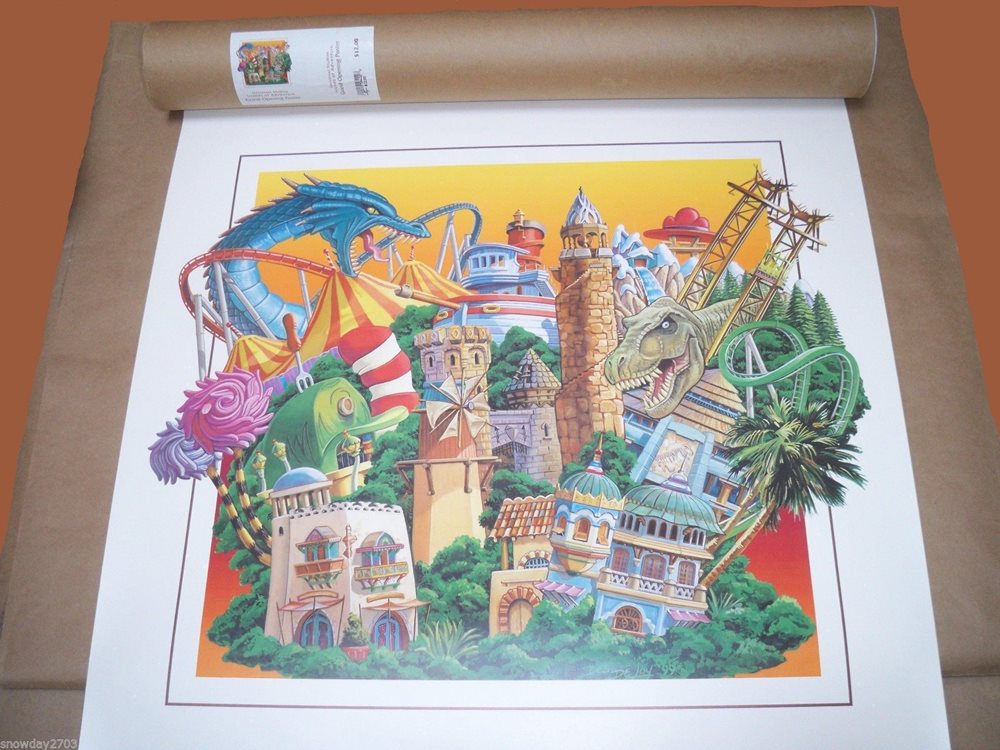

In Orlando, eyes are cast upon the birth of an unparalleled industry marvel: Universal Studios Islands of Adventure.

– In the following article a mix of images is used. All images are owned by Coaster Kings, unless states otherwise. – Over the years, many of our images have popped up on other sites and forums, awesome that our coverage spreads, not so awesome that not everyone mentioned where they got the images from. We are totally fine with our audience using our images, BUT ONLY IF credit is given to thecoasterkings.com. Thank you! –

Twenty years later, Islands of Adventure is a name still fresh on everyone’s tongues – Universal Studio’s seismic, shape-shifting thrillscape proved itself to be more than just a temporary diversion from the nearby Mouse compound. Despite the missteps, accolades are in order for IOA – the most functional and consummate theme park in Central Florida, if not the world.

The Beginning

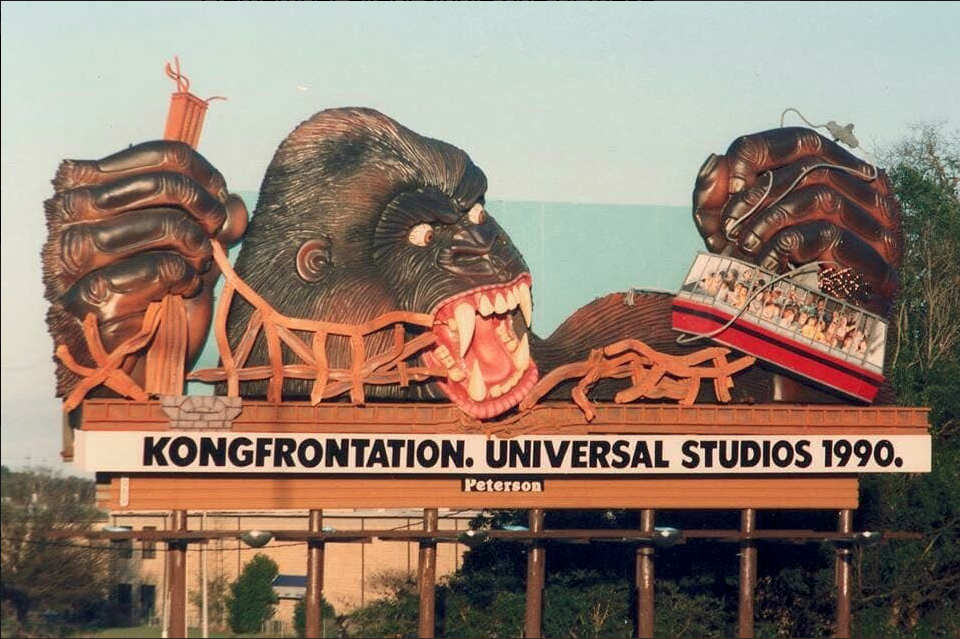

Universal Studios Florida came down with a thud in 1990 as a solid selection of opening-year attractions were decimated by technical problems. Kongfrontation and Earthquake: The BIG One were fashionably late; JAWS wound up a costly, multi year money pit that required a full demolition and rebuild (ET Adventure would be the only opening day E-ticket to arrive as scheduled). The importance of 1991’s Back To The Future can’t be overestimated: the envelope-pushing thrill ride helping steady the troubled park’s trajectory to success.

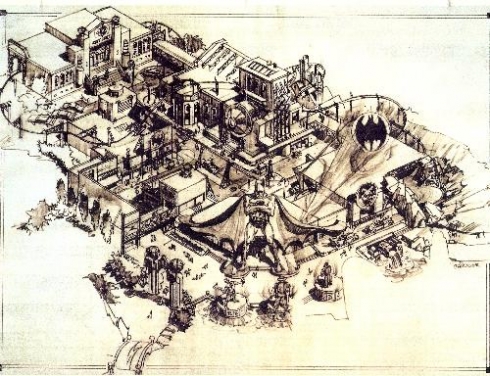

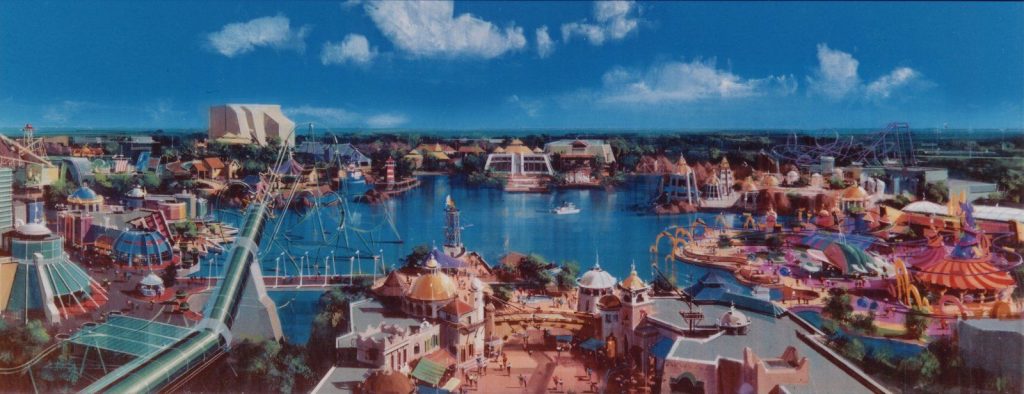

The 1993 season would be an important one for Universal Studios Florida. With a sturdy foundation of attractions (JAWS notwithstanding), it was time to start solidifying plans for a major flag in the sand: a second gate – one that would leave sound stages and real-world environs behind. Ideas flew and fizzled; fledgling park concept “Cartoon World” blossomed from a DC-Comics-anchored experience into a meta-multimedia milieu, blending beloved storybooks, omnipresent newspaper funnies, fabled fantasty-scapes, and the shiny-new box office juggernaut Jurassic Park. Luxury hotels would be the icing on the Universal Resort cake, and a ritzy entertainment district would be a cherry on top.

Walt Disney World’s MGM Studios and Animal Kingdom were carefully calculated risks – parks offering just enough to satisfy the means. Nevertheless, a lingering reputation of insufficient attractions befell the parks (and follows them to this day). With Universal Studios Florida guilty of the same in its first years, the roadmap to a successful 2nd gate was simple: do what Disney won’t – open a theme park that’s complete from day one.

Universal’s Islands of Adventure was not the immediate money spinner they’d hoped for (the clumsy “Universal Studios Escape” marketing campaign is largely credited for that), but the new park was an instant success by the measure of opening a “full day park” and making it look easy. The public took their time discovering IOA’s majesty, but industry insiders were quick to recognize the such a confident execution in a neighborhood of half-baked 2nd gates.

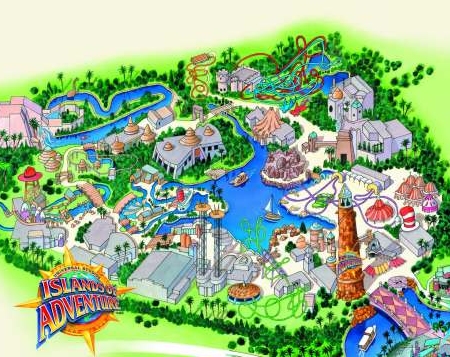

The Islands

Theme parks are often painted into a corner when they assign themselves an over-arching thematic mission. Studios-themed parks were a great way to create an immersive experience without having to flesh out a ton of external scenery (why invest in exterior aesthetic when you put something in a nondescript building and call it a “live set”?). Alas, you can’t branch out from that concept without sacrificing the premise – something that all studios-themed parks are guilty of. With that in mind, Islands of Adventure would be Universal’s vehicle for taking on the wagon wheel-shaped, mishmash park formula, complete with grown-up versions of “Yesterday, Tomorrow, and Fantasy.”

Not one, but two “islands” lack any sort of intellectual property tie in; such a move would be a cardinal marketing sin in 2019. Incidentally, “Port of Entry” and “The Lost Continent” are the park’s most dramatic landscapes – ones brimming with breathtaking architecture, foliage, and movement.

Meanwhile, the 3 original Cartoon World islands – Seuss Landing, Toon Lagoon, and DC Comics Marvel Superhero Island – were Universal’s opportunity to build cohesive themed areas without going over budget. Whimsical applications of colored concrete and wonky palm trees bent by Hurricane Andrew are the hallmarks of Seuss, while Toon and Marvel are appropriately festooned with 2D characters and scenery that narrowly avoid reading as a cost-cutting measure.

Somewhere in between is Jurassic Park: a tropical theme park area themed to a tropical theme park. Such a premise would canonically allow for some “we are unapologetically in an amusement park” atmospheric liberties, but Universal took the high road by making Jurassic Park a satisfactory response to Magic Kingdom’s Adventureland (and, ostensibly, Animal Kingdom’s dreadful McDinoland U.S.A.)

A 1999 visit to most (if not all) of Orlando’s parks was a far cry from an inaugural-season visit to the new park on the block; with the exception of Magic Kingdom and Busch Gardens, Islands of Adventure opened with more attractions than any 2 Florida parks put together. Was this completely necessary? No. Was it a little risky? Perhaps. Did it work? Absolutely.

The Rides

Speaking of attractions, Disney was always keen on touting “attraction” rosters over “ride” rosters (they knew better than to admit that MGM Studios opened with several shows and meager ride count of 2), but Islands of Adventure flipped the script: why bother with more than 1 or 2 good shows when every nearby park is routinely accused of not having enough rides? For better or for worse, IOA exploded onto the scene with an original ride roster the likes of which hasn’t been seen prior or since in the Western Hemisphere.

In an approach best described as the (over)correction of Universal Studios Florida’s early troubles, Islands of Adventure dumped a pile of checkmarks on an exhaustive list of boxes : There’s the E-ticket dark ride (The Amazing Spiderman), a C-ticket dark ride (The Cat in the Hat), live shows geared respectively to acrobatics (Sinbad) and special effects (Poseidon), the regional park water ride trifecta (a log flume, a river rapids , and a shoot-the-shoot; the latter doubling as an auxiliary marquee dark ride), an onslaught of skyline-defining signature thrill rides, and multiple areas built to provide children the opportunity to exhaust themselves. It’s a dream park for everyone, from polished civil engineers to Roller Coaster Tycoon enthusiasts, and everyone in between, but it’s not quite perfect.

With high-profile theme park debuts come a follow-up season of fixes and gap fillers (rides like Star Tours, Back to the Future, and Kali River Rapids filled large holes in their respective park’s arsenals). IOA, however, just had a few crannies to fill: Flying Unicorn helps ease the stress on the misguided capacity disaster that is Pteranodon Flyers, and Storm Force Accelatron offers the only experience in Marvel Superhero Island that won’t threaten to plunge the average 6-year-old into a state of panic (and, despite being a mere teacup ride, was the all-but-necessary X-Men-themed attraction).

As quickly as these two attractions came, two others were written out of the show : Island Skipper Tours is phased out after a few years due to disproportionate operating costs, and Sylvester McMonkey McBean’s Very Unusual Driving Machines are swept under the rug, Universal failing to acquire approval to open the ill-fated monorail attraction.

Continue on page 2 – The IOA of today.

Excellent report. Well written and read.